The History and Story Behind Our Lady of Guadalupe, Part II

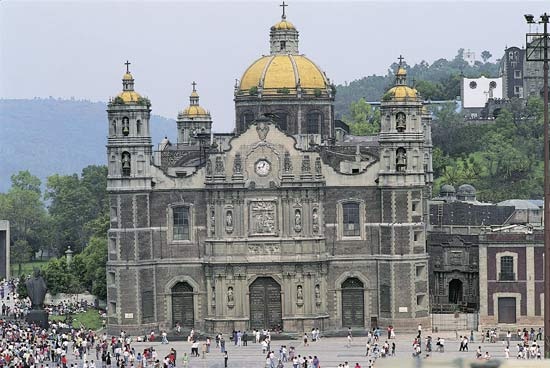

The first basilica built in 1536, Mexico City

(Continued from Part I)

Appropriating the Name Guadalupe

According to tradition, a dark skinned statue of the Virgin was carved by Saint Luke the Evangelist and given to Saint Leander by Pope Gregory I. When Seville fell to the Moors a group of priests took the statue northward through the countryside and buried it in a cave at Extremadura, along with other important items, to protect it from the Muslims who were known to destroy all Christian images. The cave was located near the Guadalupejo (now called Guadalupe) River. Leaving no records of their buried treasure it was so well hidden even the Catholics could not find it. The legend continues that six hundred years later a cow herder had an appearance of the Virgin asking him to have the priests dig where she appeared to find the lost statue. As devotion to the statue grew it became known as Our Lady of Guadalupe. Today, with Mexico's Our Lady of Guadalupe appropriating the same name the original in Spain is now called Our Lady of Guadalupe of Extremadura or Our Lady of Extremadura.

According to tradition, a dark skinned statue of the Virgin was carved by Saint Luke the Evangelist and given to Saint Leander by Pope Gregory I. When Seville fell to the Moors a group of priests took the statue northward through the countryside and buried it in a cave at Extremadura, along with other important items, to protect it from the Muslims who were known to destroy all Christian images. The cave was located near the Guadalupejo (now called Guadalupe) River. Leaving no records of their buried treasure it was so well hidden even the Catholics could not find it. The legend continues that six hundred years later a cow herder had an appearance of the Virgin asking him to have the priests dig where she appeared to find the lost statue. As devotion to the statue grew it became known as Our Lady of Guadalupe. Today, with Mexico's Our Lady of Guadalupe appropriating the same name the original in Spain is now called Our Lady of Guadalupe of Extremadura or Our Lady of Extremadura.

The name 'Our Lady of Guadalupe' at Tepeyac is probably derived from the association with Spain's 'Our Lady of Guadalupe' in Extremadura. Cortés revered Our Lady of Guadalupe, a statue of a black version of the Virgin Mary he knew from his birth town in Extremadura, Spain, at the Santa María de Guadalupe monastery. He brought an icon of her which went to the missionaries to rally the natives into Christianity. At the time of the 1556 Church investigation the dark Madonna was kept at the shrine and Guadalupe started to be used to refer to the shrine.

The Tilma of Juan Diego

The Tilma of Juan Diego

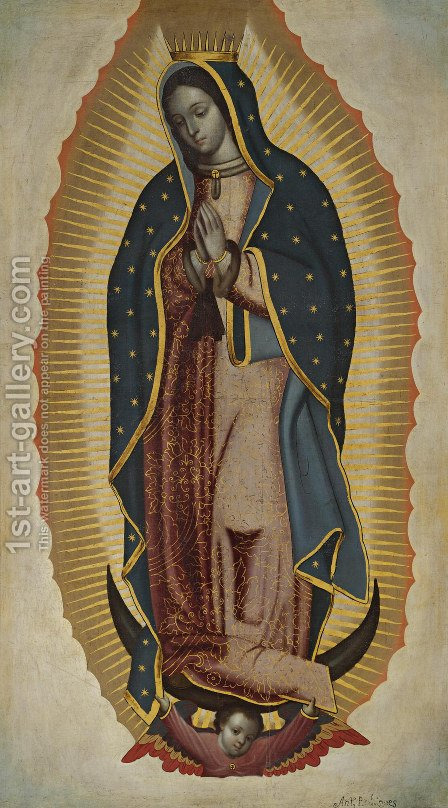

Mary's image, according to the legend, is believed to be miraculously imprinted on Juan Diego's tilma in 1531. Around 1556 we know that there was a painting of the Virgin hung in the shrine on Tepeyac Hill. (More on that below.) What history does not make clear, and the debate continues today, is the revered tilma hung in the basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe a miraculous image or a painting?

The tilma was believed to be modified, as verified by an infrared and ocular study in 1979, sometime in the 16th century and probably continuing into the early 17th century. Added to the image was a mandorla-shaped sunburst around the Virgin, the stars on her cloak, the moon under her feet, and the angel with a folded cloth supporting her. The creator of the additions to the Guadalupe icon appears to have used as a model a late fifteenth or early sixteenth-century engraving from the Book of Revelation 12:1 where John saw a woman "clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet." The virgin of the icon stands on a crescent moon, the sun's rays creating an almond-shaped mandorla, or glory, around her, with the twelve stars that crown her head in the Bible multiplied and scattered over the surface of her blue mantle.

There is also obvious cracking and flaking of paint all along a vertical seam in the fabric, and the infrared photos reveal in the robe’s fold what appear to be sketch lines, suggesting that an artist roughed out the figure before painting it. Portrait artist Glenn Taylor has pointed out that the part in the Virgin’s hair is off-center; that her eyes, including the irises, have outlines, as they often do in paintings, but not in nature, and that these outlines appear to have been done with a brush; and that much other evidence suggests the picture was probably copied by an inexpert artist from an expertly done original. But a truly scientific examination involving sampling of the material has not been permitted.

The most notable examination was a three-hour infrared photographic session by Philip Callahan in 1981, who did note multiple layers of paint covering changes to the hands and crown but came away with more questions than answers. Callahan found, for example, that most of the entire painting seemed to have been done with a single brush stroke. However, skilled artists can hide their brush strokes. In 1982, Jorge Sol Rosales, an art restorer, was asked to remount the tilma. Rosales As Rosales’ primary task was to conduct a restoration and he had all night to make his observations, albeit he did not do scientific studies except to view the cloth under microscope. Rosales offers that lightly moistening the surface of the cloth could further obscure brush strokes.

Rosales said that the tilma had been prepared with a brush coat of white primer (calcium sulfate), and the image was then rendered in distemper (i.e., paint consisting of pigment, water, and a binding medium). The artist used a “very limited palette,” the expert stated, consisting of black (from pine soot), white, blue, green, various earth colors (“tierras”), reds (including carmine), and gold. Rosales concluded that the image did not originate supernaturally but was instead the work of an artist who used the materials and methods of the sixteenth century.

Callahan recommended a series of more tests, but the only one allowed by the Church was a spectrophotometric examination done by Donald Lynn from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The only result released of his examination was that "nothing unusual" was found. However, the internet provides a plethora of false claims about the NASA tilma tests that caused Snopes to set the facts straight and has written a page about the source of the rumors and what is fact and what is not.

There was once a crown on the Virgin's head. There is a lengthy description of her image in the book called The History of the Apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe written in the Aztec language of Nahautl by Antonio Valeriano, published by Bachiller Luis Lazo de la Vega. It says on page 33, "Her head is inclined to the right; and above the veil is a gold crown whose spindle-shaped points have wide bases."

There was once a crown on the Virgin's head. There is a lengthy description of her image in the book called The History of the Apparitions of Our Lady of Guadalupe written in the Aztec language of Nahautl by Antonio Valeriano, published by Bachiller Luis Lazo de la Vega. It says on page 33, "Her head is inclined to the right; and above the veil is a gold crown whose spindle-shaped points have wide bases."

From Wikipedia:

The image had originally featured a 12-point crown on the Virgin's head, but this disappeared in 1887–88. The change was first noticed on February 23, 1888, when the image was removed to a nearby church. Eventually, a painter confessed on his deathbed that he had been instructed by a clergyman to remove the crown. This may have been motivated by the fact that the gold paint was flaking off of the crown, leaving it looking dilapidated. But according to the historian David Brading, "the decision to remove rather than replace the crown was no doubt inspired by a desire to 'modernize' the image and reinforce its similarity to the nineteenth-century images of the Immaculate Conception which were exhibited at Lourdes and elsewhere ... What is rarely mentioned is that the frame which surrounded the canvas was adjusted to leave almost no space above the Virgin's head, thereby obscuring the effects of the erasure.

If you wonder why the top of Mary's head is cut off, several inches of the mantle above Mary's head also disappeared with the crown's disappearance and with a concomitant lowering of the frame.

If you wonder why the top of Mary's head is cut off, several inches of the mantle above Mary's head also disappeared with the crown's disappearance and with a concomitant lowering of the frame.

The original image consisted of at least the Virgin wearing a blue-green cloak and pink robe, in almost exactly the same form today, though without the gold and Gothic embellishments. The fingers of the left hand originally extended farther and to the left. The face was that of a fourteen to sixteen-year-old girl, very lightly painted, using only white and shadow. The hair was more dark brown than jet black.

Callahan’s study has outlined the probable sequence of additions to the painting. First, the dark moon and the tassel, then the angel and lower fold of the robe, followed by the white background and sunburst. Then came the gold trim with dark outline in the mantle and tunic, and finally, according to Callahan, the stars. The paint in these areas, being laid thick, has cracked and peeled in numerous places. And, of course, in 1888 the crown was removed.

Damage has occurred due to the image being displayed without protection from the smoke and beeswax of votive candles until the mid-seventeenth century. Afterward, it was repeatedly exposed to be touched and kissed by the devout leading to eventually, having to repair the hands although stains still remain on them. There is a stain from where nitric acid had been spilled on it in the late eighteenth century. The field of rays are covered with countless stains, from the patina of age or accidental maltreatment. Around the head the stains are larger and seem to form figures.

The only definitely known early retouches were in the early 17th century when the cherubim was removed. The gold stars were retouched repeatedly since the 19th century. Some estimate there are been up to twenty retouches done on the tilma. Still, most of the scientific and expert analysts done on the tilma have come away with affirming that the tilma is either a miraculous image or otherwise inexplicable due to the many facets of it that they believe no artist can create such as no sizing or primer other than that of the colors themselves, was incorporated in the rough cloth and the cloth is too loose and coarse to be painted upon.

The question on what material was Juan Diego's cloth made from is still open to debate. In 1999, Leoncio A. Garza-Valdes, a San Antonio pediatrician, microbiologist, and amateur archaeologist, studied the tilma by taking infrared pictures of it. He was also given a fiber from the outer edge of the tilma. He concluded that the specimen supplied to him was made of hemp, not of agave fiber. Rosales examined the cloth with a stereomicroscope and observed that the canvas appeared to be a mixture of linen and hemp or cactus fiber.

John J. Chiment, a paleontologist at Cornell University, teaches a course about determining the age, materials and place of origin of artworks. He was invited to study the cloth of the tilma and concluded that "the tilma seems to be made from woven hemp, from a plant that is native to Mexico. This could explain the tilma’s remarkable state of preservation. Hempen cloth can last hundreds of years. It is one of the strongest fibers known."

In earlier studies the consensus among experts had been that the tilma was likely composed of iczotl, botanically known as Palma silvestre (now Yucca aloifolia), rather than maguey proper (i.e., the genus Agave). The reason for this is that the cloth was considered to be much too fine to be woven maguey.

These are all educated guesses, based on the weave and texture of the cloth. Also, the fibers that were studied were from the outer edges of the cloth and it is believed the edges are made of hemp, but not the inner part. The only chemical analysis made was done by biologist Isaac Ochoterena on a supposed 'relic' of the tilma. He concluded that the plant used for the tilma was an agave of indeterminate species. It is known that anything made from agave can only last a few decades at most.

Información of 1556

The most important document on the cult of Guadalupe during Montúfar’s archiepiscopacy is without a doubt an investigation (Información) on some thoughts on the cult that were expressed in a sermon, given by the Franciscan provincial Francisco de Bustamante in September 1556. Over the centuries the Información record has reappeared, disappeared, and appeared again, only to disappear again from the Historical Archives of the Archbishopric of Mexico in recent times. The entire investigation is revealed in Magnus Lundberg's The Archbishop and the Virgin: Alonso de Montúfar and the Early Cult of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

In brief, two sermons were given in 1556, one recorded from eyewitness testimonials, pitting the Franciscan provincial, Francisco de Bustamante (1555-1562), against the archbishop of New Spain (1553-72), a Dominican named Alonso Montúfar. Instead of replacing the Aztec goddess, Montufar’s idea was just to bring Mary by labeling Tonantzin a title and a face. Reasonably, this use of a pagan idol instigated distress among some of the Franciscan clerics. However, many of the Dominicans cheered the move as it facilitated the baptizing of many Aztecs.

In the first sermon, Montúfar effusively promoted the devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe and her miraculous reputation having, sometime during the previous year, enlarged the shrine to which he assigned a full-time priest. This endorsement prompted a heated response from Bustamante two days later. With much skepticism and a particular dislike of Montúfar, Bustamante was said to have denounced the cult’s image, saying the painting was falsely miraculous and that would only further erode the orthodoxy of Indian neophytes already confused between adoring what was on the altar made of “cloth, paint or wood” and the “true Mother of God who is in heaven,” as stated by one of the attendees of Bustamante’s sermon, Francisco de Salazar. Franciscan friar demanded that whoever was responsible for the “invention” of the miracle stories attributed to the Guadalupe image should be punished.

Bustamante’s sermon was considered so inflammatory and insubordinate towards Montúfar that the archbishop called for an investigation to determine its true content. Nine witnesses were interrogated and asked to confirm or deny on thirteen leading questions in an attempt to reconstruct Bustamante’s exact words. Bustamante had stated: "The devotion that has been growing in a chapel dedicated to Our Lady, called of Guadalupe, in this city is greatly harmful for the natives because it makes them believe that the image painted by Marcos the Indian is in any way miraculous."

Almost all the witnesses claimed the attendance was increasing both with the Spaniards and natives. One witness claimed the attendance was rising in the chapel because of the “fame of that image painted by an Indian and installed yesteryear.” In his sermon, Bustamante referred to the cult object in the shrine of Guadalupe as an “image,” but more frequently as a painting. Four witnesses relayed Bustamante’s charge that the image was painted by “an Indian” and two recalled the name of the artist as Marcos. Bustamante was relating that the image wasn’t miraculous but an actual physical painting and it was absurd to input power to a cult image. Two of the Franciscans submitted sworn statements in which they expressed their concern that worshiping the tilma was leading the Aztecs to return to their traditional pagan ways.

The inquiry, while talking about this painting, makes no mention of Juan Diego, the miraculous apparition, or any other element from the legend. Most all of the witnesses concurred with an Indian that contributed the painting, and no one disputed the Marcos link. it seems highly unlikely that the apparition could have been omitted from this report with the subject about the Marian veneration vs. the Aztec cult worshiping. This strongly supports the suggestion that the Juan Diego legend had not yet been conceived and it also supports that Valeriano's Nican Mopohua was written later than the mid sixteenth-century.

It is believed that the painting was commissioned by Bishop Montúfar, who replaced Zumárraga after his death, and the indigenous artist was Marcos Cipac (de Aquino), aka Marcos Griego, working in the 1550s. The likely reason the Archbishop commissioned the painting of the Virgin was as an aide to help convert the Aztecs and have the Christian goddess worshiped instead of their goddess. Marcos was also the name of the artist who in 1564 made the main altarpiece of San José de los Naturales, where the 1556 sermon was preached and was praised lavishly for the six-panel masterpiece.

Marcos is also praised by Bernal Diaz del Castillo in his True History of the Conquest of New Spain. Bernal speaks of the great talent by three colonial native artists. “There are three Indians today in the city of Mexico, named Marcos de Aquino and Juan de la Cruz and el Crespillo, who are so outstanding in their craft of engraving and painting, that if they had lived in the time of that ancient and famed Apelles, or of Michelangelo or Berruguete, who are contemporaries, they would also be counted among their number."

The remarkable accomplishments of painters like Marcos de Aquino constantly amazed Europeans and caused Bernal Diaz to remark that “if one had not seen them (the artworks) one would not believe that Indians had made them.”

Juan Diego's Canonization

As already noted, some Catholic scholars have doubted the existence of Juan Diego, yet when the abbot of Mexico's famed Basilica of Guadalupe, Guillermo Schulenburg, (1916–2009)) said In September 1995 that Juan Diego, the indigenous man to whom the Virgin Mary supposedly appeared 465 years ago, did not exist and that, "He is a symbol, not a reality" his words caused an uproar. In the years that followed he was vilified by the media and citizens of Mexico.

Today the country is about 90 percent Roman Catholic and a poll of Mexican Catholics found that 78 percent of Mexican Catholics have some image of the Virgin of Guadalupe in their home. Thus, the abbot's comments were seen as an attack not just on the Virgin but on Mexico itself and, needless to say, the Mexicans were very disturbed over his comments. Poole details the whole history ensuing over these years in his book, The Guadalupan Controversies in Mexico.

It began when in 1995 Schulenburg who ran the basilica for 33 years, had an interview with an obscure Catholic journal. Little notice was given to the interview until the following year when a Vatican correspondent quoted from the interview and exaggerated and distorted his meaning. In Mexico, on the same day, the Reformer published Schulenburg's interview. The whole of Mexico was in an uproar and demanded Schulenburg resign. Mexican bishops asked that Rome retire him. The news spread around the world through the wire services. In July of 1996 Schulenburg resigned.

In 1997 Schulenburg invited a number of scholars and historians, both priests and laypersons, to meet with him in Mexico City. They discussed the Codex 1548 and then the canonization of Juan Diego. They felt the process was going too fast and more time was needed to gather historical facts. It was also discussed that if the Roman Pontiff canonized a dubious person it would create a crisis of conscience as an infallible act of the papacy if ever he had to recant. And finally, the credibility of the Church would be seriously compromised. They all agreed to write a joint letter and individual ones. Stafford Poole, one of the participants not only sent his letters but a copy of his book on the history of Guadalupe.

In September 1999 Schulenburg and two others wrote a private joint letter to the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints urging a slow down the canonization of Juan Diego and warning that the Church would be made to look ridiculous by canonizing a non-existent person. Their letter was leaked to reporters and sparked another national controversy. The press was especially vicious against Schulenburg.

Again, in January 2001, along with another priest, a professor of history at the Pontifical University of Mexico, they wrote with the same warning for Pope John Paul II not to canonize Juan Diego. Again, that letter was leaked and published. In the face of centuries of devotion, and plans already made to make him a saint next year, Schulenburg said that Diego had never existed except as a tool to convert native Americans. He warned that there was insufficient evidence that the vision of a dark Madonna—adopted as Mexico's patron saint—appeared on Diego's cloak in Mexico City in 1531.

Whether Juan Diego was a real person or not, Mexican bishops were pushing Rome to move as swiftly as possible and they were backed up by many in the Vatican as well as the millions of believers in the Lady of Guadalupe. Rome was not interested in listening to any dissenters and proceeded ahead without involving any discussions with those who had contributions they felt were important to make a sound decision. Thus it was that Juan Diego was beatified in 1990 and canonized in 2002 by Pope John Paul II where an estimated eight million people lined the streets to cheer the pope.

Conclusion

Both sides of the controversy on whether the apparition at Tepeyac Hill is a true story or not have convincing points. Herein I have shared more of the side of those who see the apparition as a created myth to Christianize the Aztecs since much has been written already from believers in the apparition. As with the study on Knock, Ireland, I find many who have freely reported erroneous facts as truth and freely embellish their stories, even well-known Catholic sites, seemingly not caring to be accurate. Consequently, it takes a lot of reading from dozens of books and many more articles to uncover what is truly fact and what are miscreations or deliberate lies that are than copied over and over like the supposedly NASA researchers on the tilma (who weren't really connected with NASA) and their conclusions.

Devout Catholics are highly unlikely to turn off their devotion to the Virgin Mary no matter the facts presented. When you base your beliefs primarily on faith, which we are encouraged to do with Christ and the Bible, there is legitimate reasons to continue on in faith.

With so many disparaging remarks about the Bible and its authenticity, Christians have need to develop a strong faith. In my past, I stayed in the Teachings of the Ascended Masters by faith. I turned away from all gossip or written books or letters that talked disparagingly against the Messengers or the Summit Lighthouse all the more determined to not be "tainted" by their "distorted" views of reality. Then one day I delved in and opened my first controversial book and never looked back. I knew, without a doubt, that these people were sincere and for the most part, they were not writing out of anger or revenge, but a desire to share their truth from their personal experiences.

Although this legend of Guadalupe is not personal to me, my hope is that sharing so much detail gives those who are open to learning other facts and details other than the Catholic official version may sift through and determine from a more knowledgeable place whether it is justifiable to pray to a saint that may never have existed or pray to a mother figure who also may be a fabrication of the Roman Catholic Church. Since Catholics are programmed to believe and continually affirm they are sinners and thus need an intercessory in Mary to get to Jesus, then that is their paradigm they accept in order to have a relationship with heaven.

For those who realize we as humans sin, but we don't have to proclaim we are sinners and thereby reinforce our negative side, can and should develop a personal relationship with Jesus and look to Him for all our needs instead of praying to saints.

It is very evident from all the supporting documents providing evidence on the source and political and religious reasons for the weaving of this myth, as well as the lack of any substantial evidence that Juan Diego ever existed, that the Spanish colonial church most likely concocted the story of Guadalupe appearing to Juan Diego as a way to convert fellow Aztecs and other indigenous groups to Christianity. The tilma is the one object that is very questionable in how it has retained its integrity for the most part for five hundred years and has very hard to create nuances, even by the best painters. Yet, with God all is possible. This is just one of the many unknown and unanswerable questions in life that we will probably never know the truth.