Is Jesus Part of A Triune God?

Is Jesus part of the triune God? There is no simple answer, although the belief for what constitutes God in the Christian doctrine has been set in the formulation of the doctrine of the Trinity. The Nicene Creed is the official statement to this Trinity doctrine. It in essence states that God has three inseparable persons referred to as the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

From the earliest centuries, Christians have been divided by those who believe God is three persons in one (trinitarians); those who believe only Jesus and God the Father are God (binitarians) and some who believe that Jesus did not exist prior to His human birth but was created (unitarians). Binitarians and unitarians believe that the doctrine of the Trinity is found nowhere in the Bible while their beliefs are supported by the Scriptures. There are a few other categories that other religions have on the nature of God and therefore they deny the doctrine of the Trinity. Below are the major religions that deny the doctrine of the Trinity.

- Mormon doctrine denies the Trinity. Mormonism is tritheistic having the belief that cosmic divinity is composed of three powerful entities. Mormons believe that God, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit are three distinct deities having one purpose. They relate to each other in unique ways but are perfect in unity. They believe that God has a physical, flesh and bones, eternal, perfect body. Men have the potential to become gods as well. Jesus is God's literal son, a separate being from God the Father and the "elder brother" of men. The Holy Spirit is also a separate being from God the Father and God the Son. The Holy Spirit is regarded as an impersonal power or spirit being.

- Jehovah's Witnesses believe that God is one person, Jehovah. Jesus was Jehovah's first creation. Jesus is not God, nor part of the Godhead. He is higher than the angels but inferior to God. Jehovah used Jesus to create the rest of the universe. Before Jesus came to earth, he was known as the archangel Michael. The Holy Spirit is an impersonal force from Jehovah, but not God.

- Christian Scientists do not believe in the traditional Trinity nor are they unitarians or binitarians. Mary Baker Eddy taught, "Life, Truth, and Love constitute the triune Person called God—that is, the triply divine Principle, Love. They represent a trinity in unity, three in one—the same in essence, though multiform in office: God the Father-Mother; Christ the spiritual idea of sonship; divine Science or the Holy Comforter. These three express in divine Science the threefold, essential nature of the infinite." As an impersonal principle, God is the only thing that truly exists. Everything else (matter) is an illusion. Jesus, though not God, is the Son of God. He was the promised Messiah but was not a deity.

- Like Christian Science, Unity followers believe God is an unseen, impersonal principle, not a person. They equate the Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost with a metaphysical trinity of Mind, Idea, and Expression. Jesus was only a man, not the Christ. He merely realized his spiritual identity as the Christ by practicing his potential for perfection which all men can achieve. The Holy Spirit is the active expression of God's law. Only the spirit part of us is real; matter is not real.

- Scientology defines God as Dynamic Infinity. They have no set dogma concerning God that they impose on their members. Thus belief in God is not essential to Scientology. Jesus is not God, Savior, or Creator, nor does he have control of supernatural powers. He is usually overlooked in Scientology. The Holy Spirit is absent from this belief system as well.

- Some Pentecostal churches have moved away from the mainstream Christian doctrine of the Trinity. They believe that there is only one person in the Godhead—Jesus Christ. Oneness Pentecostals teach both that there is one God and that Jesus is fully God. They teach that the New Testament God is Jesus and the Old Testament God is Jesus by other names. The Holy Spirit is now Jesus present and acting in the One. Their philosophy closely resembles Modalistic and Monarchian Theology which holds to the Oneness working through the different "modes" or "manifestations" of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. These views of the nature of God and of Jesus Christ appeared in the second and third centuries A.D.

- Protestants are largely Trinitarians, but have rejected the Episcopal tradition, elevating scripture as authoritative. As European state religions fell into decline, Protestantism fragmented into thousands of ‘pieces’. You can now find a Protestant church that will teach any doctrine that you can imagine, although they still insist, for the most part, on a Roman Catholic trinitarian view of God and Jesus.

The Beginning Trinity

So where did these doctrinal differences on the Trinity begin? Going back to the second century it was Tertullian who coined the word, Trinity, although his definition was not the eventual doctrine it was to become. Born about AD 145 to a Roman centurion in Carthage, Tertullian was trained in Greek and Latin and became a lawyer in Rome. He converted to Christianity about AD 185 and began writing books addressing the issues facing the church of his day. In his writings he demonstrated how to use the Scriptures to refute heresies, teaching that tradition must be backed by Scripture for it to have any value. Tertullian advocated the principle that custom without truth is the only time-honored error. He is also known as the father of Latin Christianity.

Besides the Trinity, Tertullian was responsible for giving Christianity the first of many definitions. He was the first writer to use the word church to describe a specific building where people assemble to worship. He also gave us the designations of Old and New testaments saying, "All Scripture is divided into two Testaments. That which preceded the advent and passion of Christ—-that is, the law and the prophets—-is called the Old; but those things which were written after His resurrection are named the New Testament. The Jews make use of the Old, we of the New..."

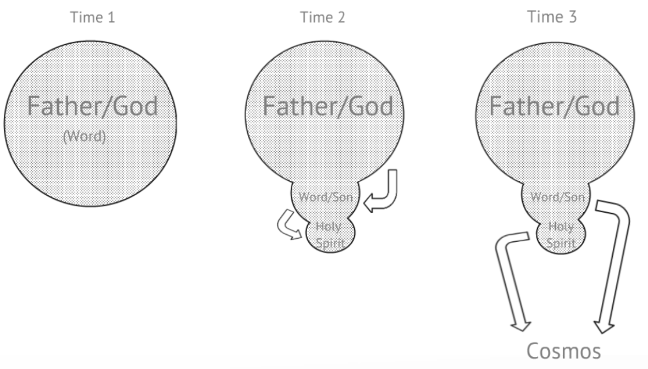

Tertullian used the word trinity to describe the Godhead. Concerning Father, Son, and Spirit, Tertullian said, “These three are one substance, not one person.” At the beginning, God is alone, though he has his own reason within him. Then, when it is time to create, he brings the Son into existence, using but not losing a portion of his spiritual matter. Then the Son, using a portion of the divine matter shared with him, brings into existence the Spirit. And the two of them are God's instruments, his agents, in the creation and governance of the cosmos. (As illustrated above)

The Son, on this theory, is not God himself, nor is he divine in the same sense that the Father is. Rather, the Son is “divine” in that he is made of a portion of the matter that the Father is composed of. This makes them “one substance” or not different as to essence. But the Son isn't the same god as the Father, though he can, because of what he's made of, be called “God”. Nor is there any tripersonal God here, but only a tripersonal portion of matter - that smallest portion shared by all three. The one God is sharing a portion of his stuff with another, by causing another to exist out of it, and then this other turns around and does likewise, sharing some of this matter with a third.

Against the common believers concerned with monotheism, Tertullian argues that although the above process results in two more who can be called “God”, it does not introduce two more gods - not gods in the sense that Yahweh is a god. There is still, as there can only be, one ultimate source of all else, the Father. Thus, monotheism is upheld. (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

To Tertullian, the "trinity" is God, His Reason and the Word as an expression of that Reason. Because God is pure Spirit, all which He does as Father is Spirit. That which extends from Spirit into flesh is the Son. Tertullian does not think of three, separated persons in the Godhead.

The Arian controversy was a series of Christian theological disputes that arose between Arius (256-336 A.D.) and Athanasius of Alexandria, two Christian theologians from Alexandria, Egypt. The most important of these controversies concerned the substantial relationship between God the Father and God the Son.

Arius had this Unitarian belief and it was the Arian controversy that set in motion the first ecumenical Council in Church history. The council of Nicea was convened by Constantine in 325 which resulted in the condemning the teaching of Arius and produced a creed which declared that the Son is of one substance with and co-eternal with the Father. Yet there is far more to the story before and after this ecumenical Council was held. While Christians were divided amongst themselves on what relationship Jesus the Christ had with God, they were being persecuted on and off by the Roman emperors. Christianity and its followers were, in certain parts of the world, driven underground for a time. Unity was impossible. There was no united doctrine until the Roman Empire intervened.

Christian Persecutions A.D. 249-311

In A.D. 249 the Roman emperor Trajan Decius issued an edict that began an empire-wide persecution against Christians. At that time the empire had been battered on every frontier by invading armies. There was absolute rampant inflation and governmental instability. For a hundred years emperors only had short reigns as they kept getting assassinated or died in battles. It's an incredibly fraught time in the history of the empire. Decius' edict required all inhabitants of the Roman Empire to sacrifice to the gods. Prior to this edict, persecution of Christians had been sporadic and were more local affairs, but afterward, Roman emperors were involved with the persecutions on an imperial scale. Decius could not carry out his edicts effectively because of his premature death in 251. After Valerian the elder became emperor in A.D. 253 he left the Christians alone until 257 when he suddenly decided to complete the unfinished work of Decius and uproot Christianity from his dominions. Historians do not agree on what brought about this sudden change of Valerian toward the Christians, but many favor the idea that Macrianus influenced Valerian to the changeabout.

The first decree also commanded Christian clergy to perform sacrifices to the Roman gods or face banishment. The decree also forbade Christians from holding assemblies, entering subterranean places of burial, and sent clergy into exile. Many were martyred at that time. Decius issued a second decree the following year, which ordered the execution of Christian leaders. It also required Christian senators and Roman knights to perform acts of worship to the Roman gods or lose their titles and property, and directed that they be executed if they continued to refuse. Christians and their leaders were literally forced underground.

After Valerian's death his son, Gallienus, became emperor and rescinded his father's edicts, whereby for the following four decades the Christians were restored their possessions and rights to worship. It was in A.D. 303 that the Great Persecution under the co-emperors Diocletian and Maximinus began. Diocletian decided that the empire was too big to manage by one person so he created a Tetrarchy, dividing the imperial power into the east and west. The Tetrarchy was composed of two senior emperors (Augusti) and two junior tetrarchs (Caesars). Maximinus was co-emperor in the west with Diocletian ruling in the east. Each had a Caesar as their right-hand man. Diocletian had Galerius (born Gaius Galerius Valerius Augustus, later emperor from 305-311), and in the west Maximinus' Caesar was Constantius Chlorus, (also known as Constantius I, co-emperor from 293 to 306) who ran Gaul and Britain and was the father of the future Constantine the Great.

Aside from the continued problems with finance and border security, Diocletian was concerned with the continuing growth of Christianity, a religion that appealed to both the poor and the rich. The Christians had shown themselves to be a thorn in the side of an emperor since the days of Nero in the first century. The problem only grew worse as their numbers increased. Diocletian wanted stability and that meant a return to the more traditional gods of Rome, but he believed Christianity prevented this.

During the Great Persecution, Diocletian began delivering edits—possibly encouraged by his right-hand man, Galerius, who later became emperor in 305 when Diocletian abdicated due to poor health. (Maximian also abdicated in 305 by Diocletian's request.) The first edict Diocletian ordered was the destruction of all churches and Christian texts and prohibited Christians from assembling for worship. Galerius took a stronger measure wanting all those refusing to sacrifice to be burned alive, but Diocletian requested that there be no bloodshed. Despite his request many were tortured and then burned alive.

Later a second edict was published, ordering the arrest and imprisonment of all bishops and priests. After the prisons became overflowing with clergyman a third edict was released stating they could now be freed, so long as they agreed to make a sacrifice to the gods. Though many did not, they were still freed under the pretext that they had completed the request. The fourth and last edict ordered all persons, men, women, and children, to gather in a public space and offer a collective sacrifice. If they refused, they were to be executed.

Nevertheless, Christians did not return to paganism or entirely stop worshiping Christianity. Witnessing the martyrs and clergy bear their burdens only spurred the Christians to see themselves following in the footsteps of Jesus, the first martyr. Undoubtedly many pagans at some of these martyrdoms were so impressed by the courage of the Christians that they came to see the truth of the Christian religion themselves and immediately converted to Christianity.

The Great Persecution came to an end in 311. Previously persecutory policies had varied in intensity across the empire. Constantius and Maximian in the west had little interest in the persecution. While Galerius and Diocletian in the east were avid persecutors. By 311, Galerius was severely ill and could have believed the condemnation of the righteous Christians was not abating their growth and that his persecution of them might be the cause of his pain and suffering. Thus he issued the Edict of Toleration, ending the Great Persecution and hoped that the prayers of the Christians would save him. He died a week later. His successor, Emperor Maximinus II, (nephew of Galerius) tried to counteract the edict but failed to any great extent in his short rule.

Diocletian’s vision of a Tetrarchy would eventually fail. It came to an end with the Christian emperor Constantine (also known as Constantine I and Constantine the Great). Constantine would eventually be the sole ruler over both the east and west.

Diocletian’s vision of a Tetrarchy would eventually fail. It came to an end with the Christian emperor Constantine (also known as Constantine I and Constantine the Great). Constantine would eventually be the sole ruler over both the east and west.

After years of war between the successors,1 Constantine reunited the empire in A.D. 324. He took part of the empire back from the co-emperor Maxentius (son of former Emperor Maximian) after the Battle of Milvian Bridge. That left himself and Licinius (son-in-law of Constantius Chlorus) as co-emperors after Galerius died from his terrible disease in 311.

How Sincere was Constantine's Christianization?

The battle of Milvian Bridge happened in A.D. 312 after Constantine saw that Maxentius’s empire in the west had begun to self-destruct. He gathered an army of forty thousand, crossed the Alps and invaded Italy. What happened next is believed to be intercession from God. Constantine's was raised by his pagan father and Christian mother, so he never was completely Christian or pagan but he had enough understanding of Christianity to be open to Christ as depicted in the following tale.

On the day before the battle began, Constantine reportedly looked to the sky where he saw the sign of the cross superimposed over the sun. Under it was the inscription In Hoc Signo Vinae or “conquer by this sign.” The sign he saw was not the cross; it had not yet become the symbol of Christianity. The Greek chi-rho monogram (depicted in the picture to the right) consists of the superimposed Greek letters chi (X) and rho (P), forming the first two letters of the Greek title “Christos,” or “Christ.” Following Constantine's vision, he had a dream according to Christian author Lactantius, writing several years after the battle. Christ appeared before him telling him to carry the sign of the cross he had seen in his vision into the coming battle. The following day old banners were replaced with new ones displaying the sign of the cross.

On the day before the battle began, Constantine reportedly looked to the sky where he saw the sign of the cross superimposed over the sun. Under it was the inscription In Hoc Signo Vinae or “conquer by this sign.” The sign he saw was not the cross; it had not yet become the symbol of Christianity. The Greek chi-rho monogram (depicted in the picture to the right) consists of the superimposed Greek letters chi (X) and rho (P), forming the first two letters of the Greek title “Christos,” or “Christ.” Following Constantine's vision, he had a dream according to Christian author Lactantius, writing several years after the battle. Christ appeared before him telling him to carry the sign of the cross he had seen in his vision into the coming battle. The following day old banners were replaced with new ones displaying the sign of the cross.

Meanwhile, Maxentius had left Rome to meet Constantine because an oracle had told him the enemy of Rome would die that day. He could not control his people for they had begun to riot against him and meeting Constantine seemed the better decision rather than laying in siege within the walls of the city. Since the bridges across the Tiber were cut Maxentius made a bridge of boats to send his men over. They met Constantine and his men in one final crucial battle between the Milvian bridge and Saxa Rubra. Although outnumbered, Constantine easily defeated Maxentius who fled back to Rome. He never made it, his body and many others were discovered floating in the river.

This victory is seen by historians as a turning point in history, leading to a fusion of church and state. Constantine immediately assumed complete control of the west. After returning to Rome as the new Augustus of the west one of his first acts was to issue the Edict of Milan, proclaiming the toleration of all religions in the Roman Empire (later co-signed by Licinius). Yet Licinius’s attitude was not conciliatory towards the Christians. He and Constantine began a war for control of the Roman Empire. Licinius purged his administration of Christians and even persecuted some private citizens with both executions and the destruction of several Christian churches. This only began to endear Christians to see Constantine more as Christ's general.

In September of 324, Licinius was finally defeated at Chrysopolis and surrendered. Licinius hoped to return to life as a private citizen which Constantine initially granted, but going back on his word, Licinius was consequently hanged. Whether Constantine was truly a Christian or not, he treated the Christians very well. He rebuilt the city of Byzantium and renamed it Nova Roma (New Rome). An alleged relic of the True Cross, the Rod of Moses and other holy relics supposedly protected the new city. The figures of old gods were replaced and sometimes assimilated into Christian symbolism. On the site of a temple dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite, the new Basilica of the Apostles was built. He also built three huge churches, St. Peter's in Rome, Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

His mother Helena was a devout Christian, and after Constantine became emperor, he sent her on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land where she had built the Church of the Nativity at Bethlehem. Although he had been a worshiper of the sun-god in his youth and while some claim he did not become baptized until his deathbed, he still gave every indication that he was a devoted Christian. He did not want conflict between the Christian and pagan religions to divide his empire.

Throughout his rule, Constantine supported the Church financially, built various basilicas, granted privileges to clergy (for example, exemption from certain taxes), promoted Christians to high ranking offices, and returned property confiscated during the Great Persecution of Diocletian, and spent enormous amounts of money from the state treasury to pay clergy. It has been said about Constantine's reign, "The rule of Caesar now has become legitimized and undergirded by the rule of God, and that is a momentous turning point in the history of Christianity."

On the Conversion of Constantine, Eusebius of Caesarea (263-339 AD), a Christian historian wrote " the thought occurred to him (Constantine), that, of the many emperors who had preceded him, those who had rested their hopes in a multitude of gods, and served them with sacrifices and offerings, had in the first place been deceived by flattering predictions, and oracles which promised them all prosperity, and at last had met with an unhappy end". The Christian God may have appeared to be the powerful one and true God. Eusebius said that Constantine made the priests of God his counselors, and deemed it incumbent on him to honor the God with all devotion who had appeared to him before his battle of Milvian Bridge. Yet some still believe that Constantine appeared to still hold on to worshiping his Sun god (Sol) that appeared to have led him to endorse Sunday, the first day of the week and a day dedicated to honoring the sun, as a weekly day of rest in the Roman empire.

While Constantine is erroneously accused of making the pagan holiday of December 25 a Christmas celebration, he was not initially responsible. Before the legitimization of Christianity in Rome, the 25th of December had already been picked as one of the possible birthdays of Jesus. Theophilus of Caesarea (115-181 AD) wrote that "we ought to celebrate the birth-day of our Lord" on December 25. Hippolytus of Rome (170-240 AD) also gives the date as "eight days before the calends of January (December 25). Within Judaism there is believed to be a belief some Jewish sages held that some holy men died on the same date on which they were conceived. Jesus was thought to have died on 14 Nisan according to the Jewish calendar. That's March 25, which is celebrated in various Christian liturgical calendars as the Feast of the Annunciation to this day—the feast of the conception of Jesus. March 25 was also thought to be the date of the Creation of the World. So if according to this theological calculation, Jesus was conceived on March 25, he would have been born nine months later: on December 25.

Pope Julius I in 320 AD specified the 25th of December as the official date of the birth of Jesus Christ, possibly because it coincided with the pagan festivals celebrating Saturnalia and the winter solstice and also to bring some unity to Christians on when to celebrate Jesus' birth. The church thereby offered people a Christian alternative to the pagan festivities and eventually reinterpreted many of their symbols and actions in ways acceptable to Christian faith and practice. Yet Julius' proclamation was largely ignored, as many Jews and Christians did not believe in celebrating birthdays, and Christmas took a back seat to the Roman pagan celebration of the birthday of Sol Invictus (the unconquered sun). The first recorded date of Christmas celebrated in Rome was in 336, although in 325 AD, Constantine introduced Christmas as an immovable feast on 25 December, possibly from church leaders lobbying him for a Christian holiday that would cancel out the pagan holidays. It did not work. Many Christians took up the partying that the pagan holidays had introduced or to just celebrated the pagan holiday instead.

The date of Easter was also set during the Council of Nicea. The Gentile Christian church still celebrated Passover, but the Gentiles began to see a need to differentiate "their" Passover from the Jewish Passover. The bishops decided to move the Christian celebration of Passover to the first Sunday after the Jewish Passover (in most years). Eastern Christians celebrated Easter on Passover. The West always celebrated Easter on a Sunday. At the Council of Nicea the Eastern practice was condemned, Church authorities essentially replaced the biblical Passover with Easter, a popular holiday rooted in ancient springtime fertility celebrations. Endorsing this change, Constantine announced: “It appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast [Easter] we should follow the practice of the Jews, who have impiously defiled their hands with enormous sin, and are, therefore, deservedly afflicted with blindness of soul … Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd” (Eusebius, Life of Constantine 3).

One other sign of Constantine's true belief in Christ was from a letter he wrote to Caecilanus, Bishop of Carthage, in 313 A.D. In it he describes his orders to Anulinus, proconsul of Africa to, "not be dragged away from the worship due the Divinity" and what Caecilanus should expect to receive. He ends his letter to Caecilanus, not just referring to the Divinity (which could be any god of the pagans) but “the Divinity of the great God.” Constantine appeared to have a sincere interest in Christianity.

Christian Division

During the days when Christ's apostles lived, the Gospel was taught with accuracy, but after their death, it did not take very long for the truth to become eroded with falsehoods. Various heretical ideas and teachers rose up from within the early Church and infiltrated it from without. Jesus even warned his followers that deception in His name was possible: “Take heed that no one deceives you. For many will come in My name . . . and will deceive many” (Matt. 24:4-5).

Little by little, inaccuracy crept in as the Gospel message of Jesus Christ became more and more popular. Many pagans became followers of Christ and with them came their different pagan ideas differing in opinion and interpretation of Christ's and the Apostles words that would become the basis for the growth of various creeds and sects. One of the earliest heresies from the 2nd century is what we today call Modalism, closely related to Sabellianism. The central idea in Modalism is to solve the differences in the Trinity by making the Father, Son, and Spirit into a single being. This meant that when the Bible talks of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit it is referring to the masks or modes that God uses to reveal himself. Thus God does not exist as the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit simultaneously. According to Sabellianism God is one person and has merely manifested himself in these three modes at various times. Sometimes as Father, sometimes as Son, sometimes as Spirit. But there is no real difference between these modes, as they are all one God. This belief was condemned as heresy by Dionysius, bishop of Rome in. 262. A few groups today still hold to this belief.

Disagreements, particular over the nature of God and Jesus, obscured what it meant to be Christian. Each church, with its own doctrine, declared themselves the ‘true’ successor to the original church and declared their rivals to be apostate. Significant differences were there between the east and western empire. The West was a Latin civilization. In that part of the empire, Latin was spoken and Latin/Roman culture dominated. The East was primarily Greek in its language and in its culture. The Eastern Church spoke and wrote Greek, while the West began to speak and write in Latin.

Christianity emerged in a world which reflected both Jewish and Greek values. The Jews believed in one unique and supreme God who created by His word. A Catholic theologian stated that Greek philosophers were questioning and seeking answers as to the relationship between a Creator-God and the world which He had made. They could not see how a finite and changeable world could come from an eternal and changeless God. They proposed the idea of a "mediating Intelligence, a first emanation of the first principle which reduced the distance between God and the world.

Christians tried to bridge the two worlds through Christ's words. They sought to find an answer that would agree with the revelation they had received from Christ. As the centuries past Christian ministers and theologians interpreted His words, along with the apostles, to mean different things. Thus by the fourth century, a dispute erupted within the Christian church regarding the nature of the Godhead, more specifically the exact relationship of the Son to the Father. It became known as the Arian controversy. Arius was a priest from the suburbs of Alexandria. He recognized the difficulty of accepting three co-equal Persons in the Godhead, and of believing that it was truly God who became Incarnate. The Son, according to the theology of Arius, was the first of God’s creations and was commissioned by the Father to create the world. Since he was dealing with many pagans the first thing he wanted was to get them to accept monotheism and to deny polytheism (multiple gods). The notion of the Trinity seemed to him nothing more than a revived polytheism. The Son was, therefore, a creature, said Arius, the first-born to be sure, but inferior to God nonetheless. A characteristic phrase of the Arians was "There was a time when He (the Son) was not."

Arius found himself in sharp opposition to his bishop, Alexander, patriarch of Alexandria, and accuses Alexander of Sabellianism. Alexander was supported by a rising young theologian, deacon Athanasius, who went on to earn the title "pillar of the Church" from St. Gregory of Nazianzus. Athanasius spent the rest of his life defending the Church’s teachings and faced hardship and exile at the hands of the vindictive Arians. (Although some modern interpretations of this controversy have made Athanasius vindictive towards the Arians, not the other way around.)

Alexander felt that if Jesus was not fully God He could not be the savior of men. Arius was summoned in 318 by a council convened by Alexander which led to his teachings being condemned and his excommunication. Yet that did not by any means close the matter. Arius then wrote a letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia complaining of being unjustly persecuted and that Eusebius of Caesarea and many other Eastern bishops had also been condemned. Eusebius responded by starting a letter writing campaign to the bishops of Asia Minor supporting Arius after Eusebius visited him.

In 323 and 324, Alexander hosted local synods (or councils) of bishops from across northern Africa whereby they denounced Arius and his doctrine. Arius fled to Palestine, where another presbyter sheltered him. A competing synod in Palestine then reinstated Arius, thus invalidating the decision of the Alexandrian synods. When Constantine became aware of the Arian troubles, he charged one of his advisors, Bishop Hosius of Cordova, (also known as Osius or Ossius) to take to Alexandria his letter to Arius and Alexander, where he urged them to reconcile their factions. Yet Constantine's trusted spiritual advisor failed to bring about a reconciliation.

Scripture itself couldn’t decide the issue because both sides were quoting it to their purposes, and in fact, the canon of the New Testament had not yet been officially decided. Constantine tried to promote unity in every way possible recognizing that a schism in the Christian church would be just one more destabilizing factor in his empire. Thus it was in 325 that Constantine decided to call a council inviting 1,800 bishops and ecumenical leaders from across the empire to discuss religious doctrines and practices to help bring unity to the Christian doctrines—all at the empire's expense. The historian Eusebius chronicled that 250 to 300 bishops and leaders came from across the whole of the fast-growing Christian world. Since Christianity was still primarily confined to the East, the majority of bishops came from that area.

The Nicene Assembly

According to the ecclesiastical historian Theodoret, the bishops entered the council proudly, while clearly visible for all to see were the scars and mutilations they had suffered at the hands of their Roman persecutors in the years before Constantine. Bishop Paphnutius from Egypt could barely walk because his knees had been crushed, and he had only one eye; the other had been gouged out by a Roman soldier for refusing to deny that Christ was the Son of God. The hands of Bishop Paul of Neocaesaria on the Euphrates were paralyzed and hideously scarred from the Roman torturers who had used red-hot irons to try to break his faith. As Theodoret wrote, the Council resembled an army of martyrs.

Constantine began the assembly with an address in Latin. He did not command the bishops to declare Jesus to be divine, he instead called upon the bishops to restore order in the Church. At one of the early sessions, he shamed the Christian leaders by producing a packet of letters he had received from many of those present, accusing others of false teaching. The emperor tore them up and threw them into the fire. It seems that the emperor himself chaired most of the sessions, and according to the procedures used in the Roman Senate, intruded himself actively in the debates. Eusebius, however, praised Constantine for the patience and fairness with which he conducted the meetings, allowing all sides to express themselves.

There were primarily three factions at the council. Arius was invited and around him were about 20 supporters. Most notable of these were two Egyptian bishops, as well as Eusebius of Nicomedia. They presented the view that Christ was of a different substance than the Father, that is, that He is a creature.

The second group opposing them were the Alexandrians, called the “orthodox” group, and were led primarily by Hosius of Cordova and Alexander of Alexandria who was accompanied by his deacon, Athanasius, This group represented the view that Christ was of the same substance (homoousios) as the Father, that is, that He has eternally shared in the one essence that is God and in full deity.

The third and largest group comprised the majority of bishops, the Origenists, were for the most part disciples of Origen. Eusebius of Caesarea led this group. A large percentage of them were not theologically trained. They were concerned with maintaining the traditional Logos-theology of the Greek-speaking Church. They agreed with the orthodox party that Jesus was fully God, but they were concerned that the term homoousios could be misunderstood to support the false idea that the Father and Son are one person, primarily because it had been used in the previous century by the heretic Sabellius and others who wished to teach that error. The Origenists were promoting that Christ is only the Mediator appointed between God and the world. They, therefore, presented the idea that the Son was of a similar substance (homoiousios) as the Father. With this term, they hoped to avoid both the error of Arius as well as the perceived danger of Sabellianism.

The bishops permitted Arius to stand and present his teachings. Arius defended his view of Christ by suggesting that the Son was a creature (albeit the first and greatest of God’s creatures), made ex nihilo. Creation was made through the Son, and hence he existed before all time, but he was not eternal. Opposition from faithful Christians began immediately, but Arius and his supporters ably rallied defenders from among some of the bishops in Palestine. Arius taught that there was a time when Christ did not exist, i.e. that he was not co-eternal with the Father, that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit were three separate and distinct hypostaseis, and that the Son was subordinate to the Father, and was in fact a "creature."

Nevertheless, their arguments found little sympathy among the council fathers, who saw the ramifications for the Christian faith should they embrace the Arian position. To declare that Jesus Christ was not truly God would be a betrayal of the faith that had been proclaimed from the earliest days of the Church. For many of the bishops, it would have made a mockery of their own immense sufferings at the hands of the Romans.

The bishops all believed the deity of Christ but how He was so was the question. For the most part, they energetically declared themselves against the doctrines Arius presented. The only effective means appearing for stopping the Arians was the inclusion of the term "homoousios", "of one substance (with the father)" which the emperor favored as suggested to him by Hosius. Its use, however, by the Sabellian bishops of Libya had been condemned by Dionysius of Alexandria in the 260s, and, in a different sense, its use by Paul of Samosata bad been condemned by the Council of Antioch in 268. Dionysius had condemned those who denied any distinction between the persons of the Trinity and those who acknowledged three separate persons. Thus most of the bishops initially objected to this Greek word and also because it was unscriptural. They finally acquiesced. The fact that the emperor had suggested it may have been a factor in its acceptance. Yet once the half-convinced "middle party" bishops returned home, they ignored the Nicene definition or substituted their own.

The only difference between "homoousios" and "homoiousios" is the Greek letter iota (similar to the English letter i) between the two halves of the words. This additional letter significantly changes the meaning of the first part of the word from "homo" (the same or identical) to "homoi" (similar). With the acceptance and use of "homo-ousios" more fully expressing the one substance of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit in the Nicean Creed.

The emperor suggested a creed be drafted. Many attempts were tried. Eusebius of Nicomedia offered a creed favorable to Arian views, but this creed was rejected. Attempts were made to construct a creed using only scriptural terms with much difficulty as they proved insufficient to exclude the Arian position. One that did get results was from Eusebius of Caesarea who offered the baptismal creed of his own church and probably of Syro-Palestinian origin. By adding the word homoousios "the Son is "one in being with the Father" the Arians could not explain it away with critical explanations.

The Nicene Creed

The Nicene Creed

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made, being of one substance (homoousios) with the Father, by whom all things were made.

Who, for us men for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; and the third day He rose again, according to the Scriptures; and ascended into heaven, and sits on the right hand of the Father; and He shall come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead; whose kingdom shall have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of Life; who proceeds from the Father [and the Son]; who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified; who spoke by the prophets.

And I believe one holy catholic and apostolic Church. I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins; and I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Conclusion

While the council was supposed to bring a close to the Arian controversy, the hope proved fleeting, for the crisis continued throughout the fourth century as Arianism made an empire-wide comeback with the help of several emperors.

The Council did triumph over Arianism but only after fifty years of continual battles fueled by changes in Imperial leadership and thus changing support for one view over the other, as well as the difficulty in theological terminology made more difficult by having to translate complex terms from Greek to Latin and vice versa.

After 350 AD the Arian sympathizer, Constantius, was sole ruler. By 357 AD practically the entire episcopacy of Christendom had repudiated the homoousios, though there were notable exceptions in the West who were persecuted for their stand (Athanasius, Hilary, Hosius). The period following Nicea was a bleak one for the Church, in which intrigue, treachery, court factions, etc. played a significant role. It was due to the influence of Athanasius, the Cappadocians, and others, that a reaction set in about 360 AD. The Arians had succeeded too well, for their formula, "Christ is of another substance than the Father," went too far in the opposite direction. By the time of the second ecumenical council (Constantinople 381 AD) the Fathers were prepared to reaffirm the Nicene formulation.

While these councils have affirmed the doctrine of the Church, as mentioned at the beginning of this article, there are still many Christian religions and Christians among mainstream denominations who do not accept the Trinity as true and do not believe that Scripture supports the Trinity. All believe they are still Christians whether they accept the Trinity or not. Is it important to our faith to accept the language of the Trinity with the many nuances of language not only from the different language translations but the cultures so far removed from today? It takes years of study to discern what the true meaning might be behind what Jesus said and did not say (all recorded long after his death) and what the apostles taught.

Yet I believe it is essential to our faith to not accept church doctrine as infallible truth without first reading and studying the Scriptures with earnest prayer, both before and after, and invoking the Christ and Holy Spirit to be one with us. It would behoove us to not only pray for oneness during our studies, but to be one with us through every moment of the day as we meet life's challenges.

Many Scriptural verses Trinitarians will use to claim the Trinity is known within the Bible and taught by the apostles and Christ. Yet there are just as many verses cited by non-Trinitarians to support their beliefs claiming Jesus and the apostles were teaching something else. Since this article is long already, I felt it was important to go over these Scriptural verses and present different sides in part II, to not only help in our personal decision to believe in the Trinity (or not believe in it), as one of the major doctrines of Christianity, but also to assist us in having compassion and understanding for the many different faiths within Christianity and why they have come about.

1According to Ancient History Encyclopedia the battle for Augustus led to warring among the Roman Tetrarchy after Diocletian's death. "With the death of Constantius and the success of the war in Britain, many expected Constantine [the Great] to be named the new Augustus in the west; however, Severus (Caesar and close friend of Galerius) was promoted to the position, despite the claim that Constantius had named his son as Augustus on his deathbed. Regardless of the official decree, Constantine was declared Augustus by his men. Galerius, however, refused to recognize this declaration, naming himself Caesar instead. Not to be overlooked, Maxentius, who had also been overlooked in 305 CE, ignored both Galerius and Constantine and declared himself Augustus in October of 307 CE."